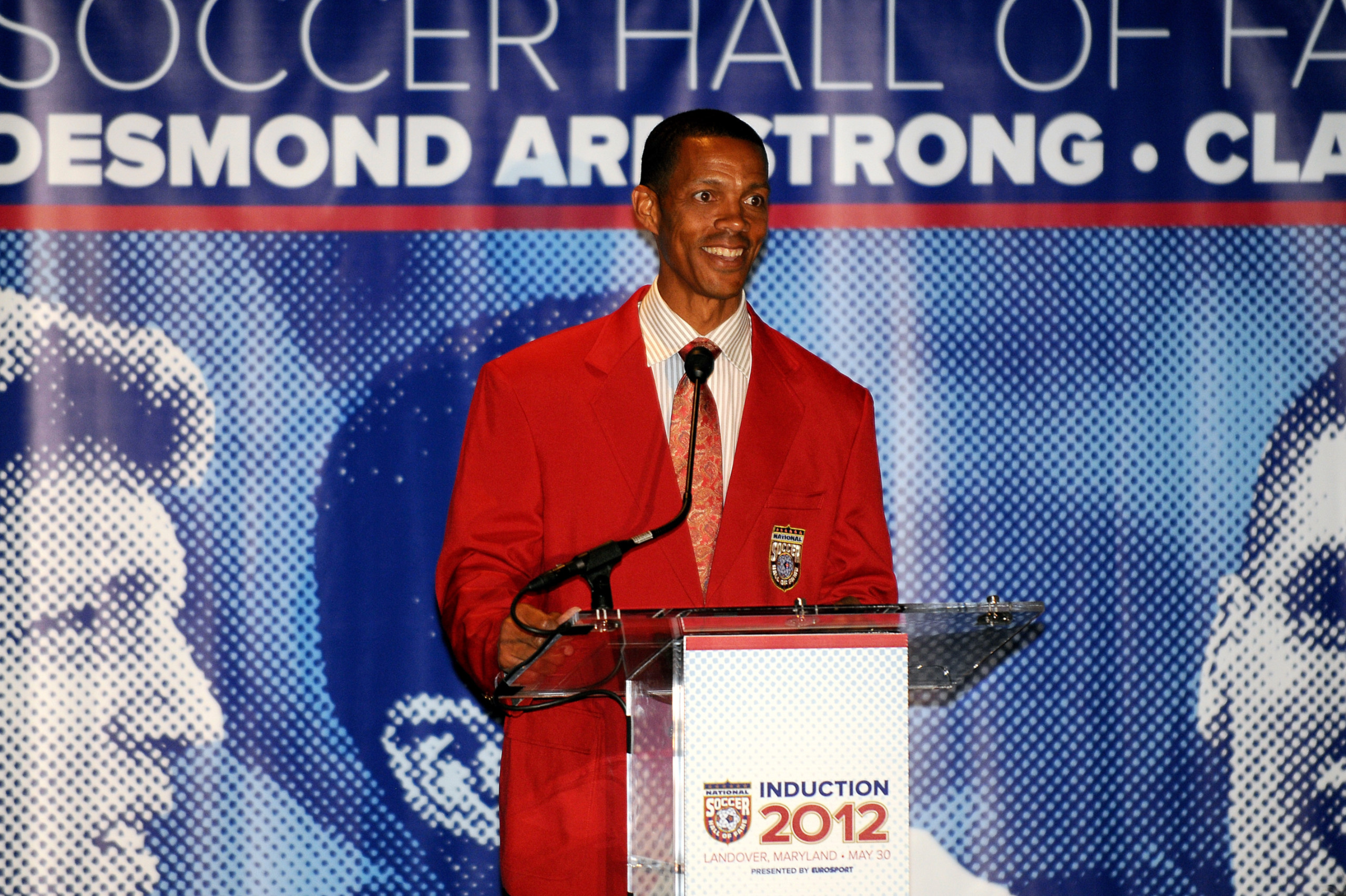

Credit: Jose L Argueta - ISIPhotos.com

Desmond Armstrong: Pride in being a trailblazer

By Charles Boehm – WASHINGTON, DC (Feb 23, 2024) US Soccer Players – Even more than four decades later, Desmond Armstrong remembers clearly how he stuck out playing youth soccer in the 1970s and early ’80s.

“At the state level… state tryouts, I was known as ‘Black Boy.’ Literally,” Armstrong recalled in a recent conversation with USSoccerPlayers.com. “I looked over the shoulder of one of the coaches, one of the assessors. I don’t know who he was, but I looked over to try to see if they’d got my name down, and got my number down. And ‘Black Boy’ was my designation. That’s at the state select level. Then at the regional level, national level, ‘Greased Lightning,’ that’s me. That’s my description.”

It was one of many such moments he experienced as one of American soccer’s pioneers.

Born in Washington, DC, Armstrong spent much of his childhood in the region’s suburbs, where he was a rare Black player in a sport widely associated with the white middle and upper classes, outside of a few immigrant enclaves. Those were the first steps of a groundbreaking career that took him all the way to the National Soccer Hall of Fame.

Armstrong advanced to a starring role at the University of Maryland, then made a name in both the indoor and outdoor circuits in the hardscrabble era between the death of the North American Soccer League and the birth of Major League Soccer.

When coach Bob Gansler named him in the starting XI for the Yanks’ opening match at the 1990 World Cup in Italy, a date with Czechoslovakia in Florence, Armstrong became the first Black player born in the United States to represent the nation in a World Cup. He was soon joined in that distinction by Jimmy Banks, a defender from Milwaukee who started the USMNT’s subsequent group stage games vs. Italy and Austria.

Banks would return to his hometown and dive into youth outreach, starting a Boys & Girls Club league and a competitive club and coaching at the Milwaukee School of Engineering. He passed away in 2019 after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Three years later a stadium in the city’s public schools system was renamed in his honor in a tribute to both his achievements as a player and his grassroots coaching work.

Armstrong carries frustration with the barriers they faced, but also fierce pride in being a trailblazer. He would earn 81 career caps for the US, a journey that helped lay a foundation for the current generation of USMNT stars who reflect the full diversity of the country in ways that were practically unthinkable back in the old days.

“Our national team is a better reflection of what America is and so I think that we are growing,” he said. “I’m encouraged that we have, or at least in this case, Gregg (Berhalter) has an opportunity to have so many more pieces to work with. As opposed to back in our day, we were the best in the country, just by virtue of, we were babies of the NASL. So we still had a burning desire to compete at a high level, even though there was nothing necessarily here in this country. And there were so few of us. Now flash to today, there’s so many more players to select from.”

Armstrong points to the rising MLS-based talents who played in the January camp friendly vs Slovenia as an example of a wider, deeper talent pool. Armstrong’s sons Ezra and Dida are currently professionals who play for USL Championship side North Carolina FC and St Louis City 2 of MLS Next Pro, respectively.

Yet the particular challenges that complicate the path for Black players and coaches remain. He points to the shorter tenures of Black coaches in MLS like Ezra Hendrickson and Robin Fraser, and laments the lingering obstacles that pay-to-play youth soccer presents to children from disadvantaged economic backgrounds.

“My recollection is, as I tell my own sons, we’ve got to be 10 times better in order to be in the conversation. That’s just the way it is,” said Armstrong. “There’s no mistaking, because it’s out in front of everybody on the soccer field, everybody can see it, you can’t deny it. … The moment that you walk in thinking it’s all equal – it’s not all equal.”

Armstrong works to address structural inequities via Nashville Heroes SC, a non-profit youth program he founded more than a decade ago to make the game more accessible to all communities in the rapidly-growing region. By soliciting donations and partnering with local businesses, Heroes keeps expenses low and covers costs for families in need.

“There are kids that are in the city that don’t play, that we just haven’t tapped into. It’s just the bottom line,” he explained. “Why haven’t we tapped into them? Because it costs so much money. Youth sports in America across the board costs money. But when we’re talking soccer, comparatively in other countries, the professional teams go in and scout the top youth players. They sign them up. They become registered players for that club, they become the property of that club. They develop that property, that talent, they use it for their first team or they sell it. That’s the business model. Over here, the business model doesn’t work that way.”

Armstrong pounded the pavement in his early years in Nashville, building relationships in working-class neighborhoods and connecting with youth in their diverse populations.

“I had like five apartment complexes that I frequented when I first got here,” he said. “We had kids from Myanmar, we had kids from Mexico, Kurdistan, Iraq, Syria, Congo, from all over. And I did a summer futsal league… they would take out the basketball court or the tennis court. And then we’d play futsal. Show up every Saturday and we’re going to do it right here. Don’t worry about transportation. Let’s pick your team. And boom, everybody plays, everybody’s there. So my piece is, let’s take this rec program to them.”

Having also coached and scouted extensively at competitive levels in Nashville, DC, Huntsville, Alabama and Ohio, Armstrong has an eye for talent. He has played a role in the development of several future professionals, including Sporting Kansas City midfielder Felipe Hernandez, a Nashville product who joined SKC’s academy in 2014 via an affiliation with Armstrong’s club and eventually signed a homegrown contract. Now, he looks out for promising youngsters in Heroes SC programs who might be ready to move up.

After so many years at grassroots level, Armstrong doesn’t sugarcoat the extent of the work that remains to be done to advance American soccer closer to fulfilling its potential. He does, though, see massive opportunities as the current USMNT group matures together on the road towards the 2026 North American World Cup, a process he’s watching closely.

He’s eager to see his old team blossom into genuine contenders on the world stage with their own style and personality.

“Optimistically, I think we’ve got a chance to create an identity, distinctly American,” said Armstrong. “We need to go into these types of games with almost like the American bravado, saying, I’m not scared of you. I don’t care what your history might be. I’m an American, and I came to show you what I got. So I’m not daunted. I’m not looking for your approval…. We need that sort of attitude to step on the field, that type of identity.”